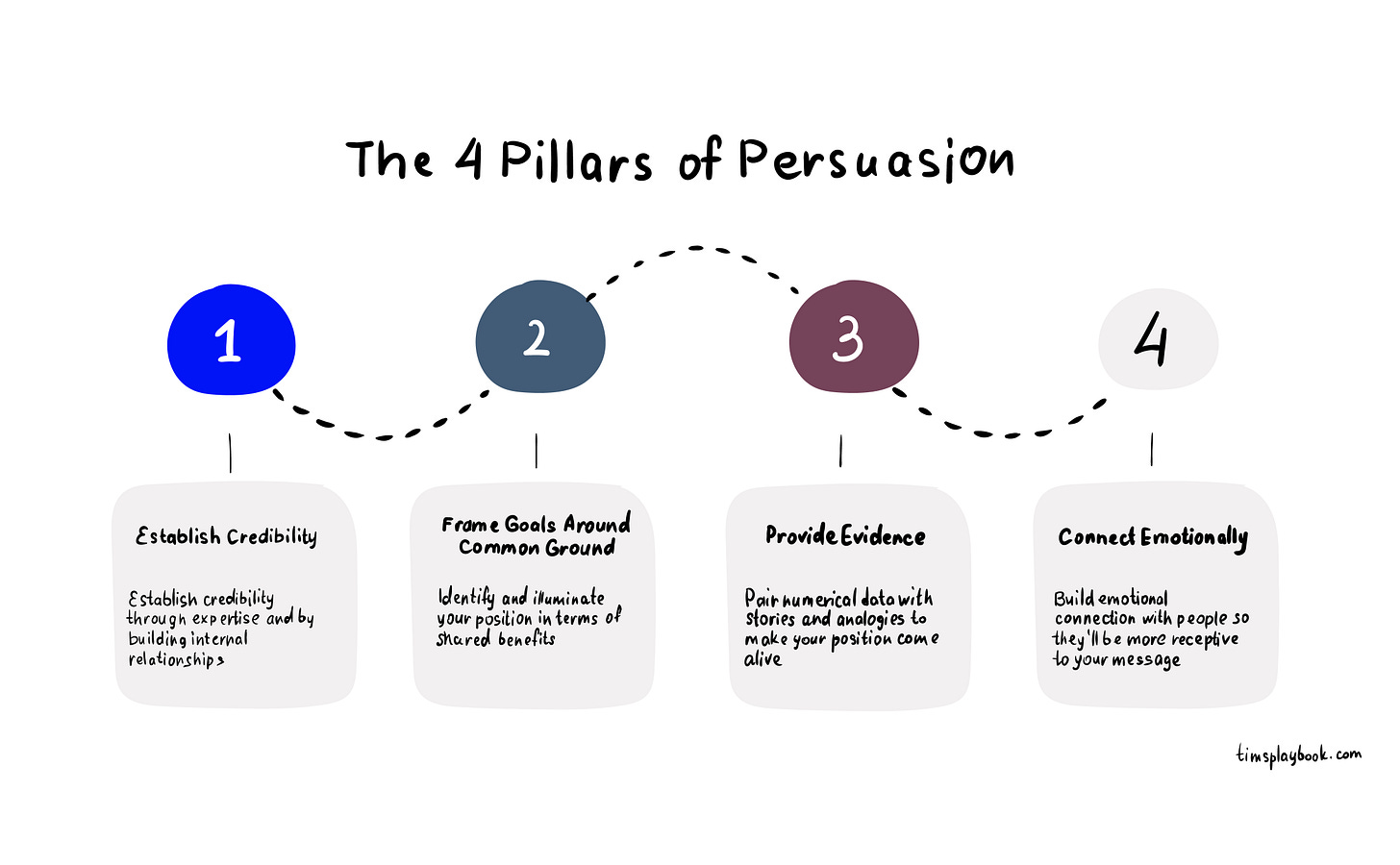

The Four Pillars of Persuasion

How to motivate your team and gain lasting influence

I write a continuing series on leadership, management, and the future of work. Each piece addresses the real questions facing first-time managers, seasoned leaders, and executives alike. Drawing on my experience as a tech leader - and the insights of my network - I share answers that are practical, actionable, and easy to put into practice.

While we might be enthralled with the advances in AI, the reality is that we’re all still very much in the business of people. This is true whether you’re making software or sponges.

For that reason, you need a strong foundation in how to influence how humans think and process information rather than machines.

Yet most people fundamentally misunderstand and undervalue the power of persuasion in the context of their professional (and sometimes even personal) lives.

We’ve gone from a top-down, hierarchical-driven environment where the emphasis was on the “What should I do” to one which is centred on the “Why should I do it.”

To answer the “Why” question compellingly, you’ll need to learn and develop the art of persuasion. While there is no shortage of books and articles on this subject, one of the best resources that I’ve come across and relied on in my career is from an article called “The Necessary Art of Persuasion” by Jay A. Conger that appeared in the Harvard Business Review in 1998.

I’ve pulled out the key themes and research from his article below and shared some examples from my professional career that will hopefully help sharpen your own skills of persuasion.

Establish Credibility

The first critical pillar involves credibility. Specifically, yours. If you’re going to advocate for a new project, idea, hire or equivalent the question becomes whether you’re qualified to take such a position. Your team will weigh the risk of supporting your idea with the relative strength of your perceived credibility.

Herein lies the challenge: most managers considerably overestimate their credibility.

When it comes to developing credibility within an organization, it typically derives from two sources:

Expertise: Do you have a track record of making strong decisions as it relates to your proposal or do you have a particularly in-depth understanding of the subject matter? Even better if you have both!

Relationships: When it comes to relationships, people with high credibility in an organization have demonstrated (often over a sustained period) that they have a high degree of integrity, consistent performance, and trustworthiness. These are typically people who put the team or goal first and are not known for politicking.

If you’re looking to develop one or both of these areas, Conger’s research pulled out several practical steps you can take.

If you’re looking to grow your expertise, you can:

Leverage your internal network: Gain more specific knowledge about your position from others who’ve done it before. You can also be asked to be placed on projects where there’s an opportunity to bolster your experience in a short amount of time.

Hire for complementary skills: You can either hire someone full-time on your team to complement your own skill set or bring on a consultant or industry expert on a more short-term basis.

Start small: You pilot your ideas to small groups to provide initial proof of concept or early results that can provide the learnings and justifications to go bigger.

When it comes to bolstering your relationship gap, consider:

Meeting one-on-one with everyone: This is the “meeting before the meeting” and gives you a chance to understand people’s perspectives and where their objections might come from.

Involve like-minded coworkers: This is a more targeted approach, but seek out people who already have a strong rapport with your audience and either enlist them to join you as part of the pitch or leverage their insight to better tap into their mindset.

Frame Goals Around Common Ground

While your credibility may be high, you’ve still only solved one piece of the puzzle. At this stage, you’ve got to make sure that you can articulate the benefits of your position in a way that makes the advantages of it clear. This is sometimes easier said than done given the benefits might not be shared amongst everyone. What may benefit you, may not benefit someone else.

I once joined an organization as a senior leader and realized that we needed to make a pretty drastic change to our existing roadmap. While I had credibility as a senior member of the team, this alone wasn’t enough to sway the minds of the many cross-functional teams it was going to impact (including our parent company).

To move my proposal forward, I anchored it to something that everyone could agree on: improving our customers' lives. We had an internal measurement of this and it had been going down slowly, so my position was that we weren’t delivering on our mission! If we continued to do the same thing we were doing we were not going to be successful as an organization.

We were all in on the company mission so this had a disarming effect on the discussion. Rather than instant scepticism, this was replaced by a real debate and discussion about what we could potentially do as a team. This meant that the original proposal was much improved, given all the additional input from the rest of the team.

Provide Evidence

“In God we trust, All others bring Data”

~ W. Edwards Deming

You’ll also need to provide data to support your point. There’s rarely a situation in today’s information-heavy workplace where a position supported by a “feeling” will take root.

Instead, you’ll need to present evidence that supports your position. However, what Conger makes clear though is that data alone won’t do:

“We have found that the most effective persuaders use language in a particular way. They supplement numerical data with examples, stories, metaphors, and analogies to make their positions come alive. That use of language paints a vivid word picture and, in doing so, lends a compelling and tangible quality to the persuader’s point of view.”

In other words, you’ve got to tell a compelling story to make the details come to life. One way to do this is to illustrate your point by using examples comparable to the one under discussion.

For example, if you’re looking to make the case to launch in a new market, are there previous examples of successful market launches at your company that you can point to or similar examples in the market at large?

Several years ago I was responsible for making the case to launch a completely new product in a relatively new market. In other words, an uphill battle from the start. The team did an incredible job pulling both internal data that showed there was a demand for the product (as well as external data), but it was when we framed it as the “international” version of a very well-known and commercially successful app that everything clicked and we got the project approved. The data alone wasn’t enough, but together with the story, it was enough to help the team vividly imagine what this launch could mean for our users.

Connect Emotionally

“In the business world, we like to think that our colleagues use reason to make their decisions, yet if we scratch below the surface we will always find emotions at play.”

~ Jay A. Conger

When it comes to connecting emotionally there are two important components to consider. Firstly, showing emotion is important. If you come across as sombre or disinterested, people will take that to mean you don’t believe in the very point you’re trying to make. Yet, if you’re too emotional you’ll leave your audience thinking you’re almost too invested and you’re not thinking objectively.

Secondly, and more importantly, Conger argues, is that effective persuaders have a keen read on their audience’s emotional state. That is to say, they adjust their tone depending on the situation. What’s more commonly referred to as “reading the room”.

In practical terms, this might mean adjusting your tone (from a whisper to coming on much more strongly) to maximise the emotional connection.

To do this well, great persuaders will lay the groundwork for this well in advance of any meeting. They tend to be very good at picking up “signals” from their peers and colleagues in informal settings (e.g. lunch break, coffee run) or by understanding how previous pitches were received and making the necessary adjustments.

What to Avoid

While the above will give you a very strong blueprint, it's sometimes as important to know what to avoid than what to specifically do.

From Conger’s research, he points to 4 things to avoid losing your audience:

Don’t hard sell. Managers too often try to force their point of view through pure logic. This often just gives someone a big target to disagree with. Instead, focus on partnering rather than selling to get your point across.

Don’t resist compromise. Your audience will want to know you’re flexible, which will add to your credibility. You’ve got to both listen to other points of view and incorporate them.

It’s not just about a great argument. As in the above examples, it’s not just about a great idea or great argument. You’re being evaluated on your credibility and ability to connect emotionally as well.

Effective persuasion is not a one-off effort. “Persuasion is a process not an event”. In other words, don’t anchor success around your ability to persuade your audience right away. It may well take several conversations (as well as iterations) to get there.

One-on-One Coaching

Alongside writing, I coach a small number of leaders each year. Availability is limited, but if I don’t have room - or if I’m not the right fit - I’ll gladly recommend trusted coaches and point you in the right direction.